Oliver Chang

Runner, CS PhD Student, and baseball nerd - but not necessarily in that order. Multiplication need not apply.

I am interested in neural networks, statistics, and robotics. I like using R and Python for statistical analysis and Java for software engineering.

I am currently a 1st year PhD Student at UCSC, studying computer science. Outside of school, I run cross country and track & field and watch Dodger baseball.

Feel free to checkout my resume and my transcript.

Reality Gap

Name:

Crossing the Reality Gap

Group Members:

- Tony Revilla

- Max Rose

- Oliver Chang

Final Project

Abstract

While training robots to navigate autonomously is a growing area of research, collecting large and diverse datasets from real environments is expensive and time-consuming. We seek to alleviate this problem by creating an autonomous agent trained inside a simulation created with Unreal Engine. We first create a dataset of over 10,000 images taken from within the simulation. Then, we use this data to train a model using different architectures to determine which one performs the best inside of the simulation. Finally, we evaluate the model’s performance in a different simulation to determine if the learning can be generalized. We found that the model trained on our data set could make it through a considerable amount of the mazes simulated in Unreal Engine, but failed to find similar success in other simulated environments.

Introduction

With improving technology, graphics processing units (GPUs) are utilized more in computer graphics. One field that has reaped the benefits of GPU improvement is simulations. Physics simulations that required data parallelism and intensive computation are now more accessible than ever. One application of simulation is in autonomous navigation. The high cost of building and maintaining a robot that can autonomously traverse terrain makes it challenging to implement computational intelligence. One way to test artificial intelligence in robots is through simulations. We are interested in examining neural network performance across different simulations and real life. In particular, we are looking to see how an agent can traverse a maze using a neural network (NN). We want to observe a robot learn to navigate a terrain, identifying a path to reach a goal.

NNs are useful in that we can feed in images to a model and have it return a direction for which a robot can interpret and move accordingly. For this cross-simulation experiment, we have selected a handful of architectures that were trained in a Raycast simulation. We believe they will cross the reality gap best in the Unreal simulation. Such architectures include ResNet, AlexNet, and an original architecture that takes an image and concatenates the previous command string. The Unreal simulation serves as a proxy for how well the models might perform in real life. First, we train models in the Unreal simulation and see how they perfom in the environment they were trained in. After, we train models in the Unreal simulation and observe their performance in the raycasting simulation.

Related Works

Neural Networks have been shown to be effective at navigating agents in different environments. However, successful training of the model often requires large quantities of training data, and in many scenarios gathering this data with real world testing may be difficult. Therefore, many researchers have attempted to create synthetic data of their specific environment in order to train more complicated models. This has shown to be an effective training method in many cases.

Weichao Qiu and Alan Yuille created UnrealCV, a tool built on Unreal Engine 4 that allows researchers to build a virtual world, and then extract the information collected by an agent in that world to be used in a neural network. This model can then be used to send information back to the agent to perform tasks in the virtual world.

Chang et al. built a simulation to collect data to train many models to evaluate their resulting behaviors. The data was collected from the simulation, and different data collection techniques were studied to determine the most effective strategy. It was found that the models performed well in the given simulation, they fail when the simulation environment is altered in various small ways.

Deitke et al. introduces RoboTHOR, a platform that helps develop and train agents on various AI navigation tasks in simulated environments and enables testing in both the simulation and the real world. The paper discusses the many challenges associated with the nature of transferring learning between real and simulated worlds. For this project, we seek to tackle this challenge demonstrated in the paper. Specifically, we turn to UnrealEngine to provide a high quality simulation environment to ease the transitions. We are interested in seeing if the lighting and higher quality graphics from the game can help the neural network travel through the maze in real-life in similar settings.

Methods

Simulation

We create multiple simulation environments in Unreal Engine, in the form of mazes. These mazes consist of a starting point, an end point, and walls forming a path between these two points. The walls are simulations of brick walls, and the floor is a black and white tiled floor. There is no ceiling, so a simulation of a cloudy sky can be seen above. At intersections there are triangles on the wall, with the point of the triangle indicating the direction the agent should take in order to make it to the end of the maze. Each maze is constructed using the same design, the difference is the placement of the walls, making the path different for each one.

Each maze is an MxN grid for some integers M and N. The path through these mazes are generated using the growing tree algorithm. Here, a cell in the grid is selected at random and added to a list. Then the algorithm selects a cell at random from the list and creates a path to an unvisited adjacent cell and adds it to the list. If there are no unvisited adjacent nodes, the cell is removed from the list. This is repeated until all cells have no unvisited adjacent cells, at which point the algorithm has completed. This algorithmically creates random mazes for the agent to move through, each one likely different from the rest.

This simulation is accessed through a connection to UnrealCV. From this tool, we can control the agent in the simulation through commands, as well as extract the current view of the agent in the form of images. In doing so, the simulation can be controlled programmatically with no need for live user input.

Data Collection

Data is collected by having the agent move along the path through the maze. We used an automator written for the raycasting-simulation by Jared Mejia. Jared’s code basically solves the maze, but the turn angles are not perfect 90 degree turns. We induce some noise so that the automator moves in a slant. We were tasked with adapting this raycasting automator such that it worked in the unreal maze. We did this by writing an Unreal object class that has built in method to translate coordinates. This was a necessary step because the unreal coordinate system is flipped on its x-axis compared to the raycasting coordinate system. After, we adapted the code we collected data. The agent only has three different movement options. “Forward” moves the agent a small distance forward in the direction that it is facing. “Left” and “Right” rotates the robot a small amount left or right, respectively. Using these options, the agent makes its way through the maze, collecting images after each movement. These images are then labeled with the decision it will make next and then saved.

The agent does not move perfectly through the path centered between the two walls. Instead, the agent moves through the path with a small amount of error added, in order to make sure that data points are collected at different positions from within the maze. To do so, the agent veers a slight amount left or right from the true path. From this, the agent does not always move parallel with the walls, and often gets close to one side or the other. In the data collection, this method was not always perfect, and sometimes (very rarely), the agent would move through corners of walls. This data was left in the data set to simulate imperfect data or to learn from situations where the agent may steer itself off course.

Using this method, we collected over 10,000 images through 10 different mazes, or about 1000 images for each maze. Each of these images are saved with a label indicating what action was taken during the data collection.

Training

We trained models on the standard CNN classification paradigm. From previous research, we found that XResNeXt18, XResNeXt50, AlexNet, DenseNet121 performed the best in the raycasting-simulation. We train unreal engine images on these neural network architectures. We also included a ResNet34 model because the ResNet is a well-regarded vision architecture. . Since we put the class label in the image file names, we need a function to retrieve those labels. The function filename_to_class does just that; it will get the angle in the filename and assign the label left, right, or forward.

We used FastAI’s library for model training. FastAI is a wrapper library of the PyTorch machine learning library. This allowed us to write succinct code and have FastAI handle optimizing the nuanced detail in model training. For dataloaders we used the ImageDataLoaders.from_name_func class. This class takes in the path to the files, file to label function, and validation percentage. The dataset was split into training and validation sets with validation getting 20% of the data. The models were trained on the same dataloader because we are concerned with architecture performance. When using the cnn_learner class from FastAI, we specified the architectures but passed in the same dataloader and set pretrained to True five times. In other words, we instantiated five cnn_learner objects, each with a different architecture. After, we fine tuned, that is trained, each model for eight epochs and exported them as pkl files.

Testing

We constructed a testing apparatus to examine model performance. We care more about the model’s image processing capabilities than path finding. That is why mazes generated in the Unreal simulator are marked with arrows to indicate the correct path. A model that performs perfectly should be able to traverse through the maze only relying on determining when to move left, right, or forward. To measure how far a model got through a maze, we utilized a function, written by Professor Clark, that uses breadth first search (BFS) to calculate maze completion percentage, that is how far along a model made it through the maze on the correct path. This is our main metric we use to evaluate our models. We initially viewed confusion matrices to gauge model performance. However, confusion matrices give a surface level idea of how a model would perform.

There are ten validation mazes. To measure model performance on the validation mazes, we wrote a nested for loop. The outer loop iterates through the models, and the inner loop iterates through the mazes. Inside the inner loop we call Imitate. This function takes in a model and a maze and does the actual predicting. Imitate is essentially a while loop that predicts what move the robot should make (given an image of the current robot’s point of view) and apply that move. After moving, we get the updated POV image and pass it into the model. We continue this process until the model reaches the end of the maze, gets off the correct path, or accidentally induces an infinite loop. Exiting the while loop runs a code block that writes the model name, maze name, and percentage completed to a csv file for analysis. This evaluating framework works for Unreal models trained in Unreal, and it should work for future assessment on models trained in the raycasting-simulation.

Discussion

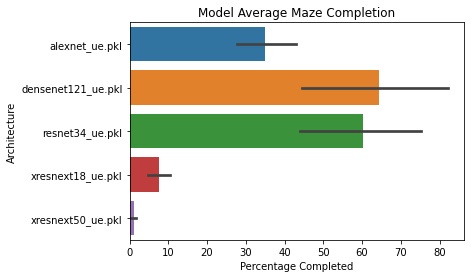

We will present a bar plot that shows average maze completion for each model, using the BFS completion metric discussed in the previous section. For the Unreal models navigating the raycasting simulation, we present a movie of the DenseNet Architecture navigating a raycasting maze.

The bar plot presented shows average maze completion for the five models in the Unreal simulation. Each bar displays a 95% confidence interval for the true mean. Observe that the DenseNet121 architecture performed the best out of the five, averaging at ~65% maze completion. ResNet34 is the runner up averaging 60% maze completion. Note that DenseNet121 and ResNet34 have wide confidence intervals. This suggests higher variability in maze solving. Even though there is higher variance, DenseNet121 and ResNet34 could navigate further than XResNext18 or XResNext50 on the same maze.

We then test our model in the raycasting simulation and found that the agent was not able to make it through most obstacles. The movie below demonstrates its performance. We see that the Unreal model starts off good. It recognizes that it must go down the corridor in a straight line. However, once it reaches the corner the model fails to turn left and runs into the wall.

Our work can be directly compared to the ARCS lab’s research they conducted over the summer. A key difference is the success in different architecture types. DenseNet121 and ResNet34 are both models with many layers that take a long time to train, and they performed the best in the Unreal simulations. In DenseNet121 each layer is connected directly with each other. ResNer34 is very similar to DenseNet, however the layers are not fully connected to each other. XResNext18 and XResNext50 essentially add more information vertically in the layers but are still similar to ResNet models. AlexNet is an early CNN, utilizing ReLu. However, initial results from the summer paper show that smaller networks with less layers actually outperformed networks with more. This difference in maze traversal can stem from the fact that our models were trained on 10 times less images than the raycasting models. This project shows that models trained in their respective environments perform better than cross-trained models. Even though unreal models did not solve mazes as far as raycasting models, there is some evidence that suggests cross adaptation is a feasible learning method. The DenseNet model managed to travel in a straight line without getting stuck in a loop. The architecture’s use of features from all complexity levels could be advantages in scenarios where data is limited.

Reflection

If this experiment were run again, we would collect more images to train off of. We believe that 10,000 images may not be enough to successfully train our agent. We would also like to improve the “wandering method” for the data collection to be more suited for the Unreal Engine environment. If this were working more consistently, it would be much easier to create a larger data set in the future.

Further work includes testing this simulated model in different environments. For example, we would like to test this model in a real environment modeled after the one in the simulation to analyze how well training on simulated data works in the real world. We would also like to test our model more in different simulated environments, as well as test models trained in other environments inside of our simulation in Unreal Engine. We would hope that our model created from simulated data could eventually be trained to a level where it is effective in real situations. Other future work involves creating a more diverse and realistic simulation, including different wall types and textures, as well as simulating more realistic places such as streets and cities.

Lastly, we would evaluate different neural network paradigms. An RNN or command image hybrid model would be ideal for maze navigation because they have some internal memory. Thus, it would not get stuck in a loop as easily.

Ethics

During our research we kept in mind several ethical concerns that could arise when utilizing simulation for the training of autonomous robots/agents. In general, there are several ethical concerns that arise concerning the use cases for autonomous robots. One concern could be utilizing autonomous robots as weapons of war or for purposes of destruction. Autonomous robots have the ability to cause harm if leveraged to do so. Even if properly utilized for war, given the black box nature of deep learning, there is not a complete confident understanding of what decision the autonomous robot will make when presented with a novel, unknown scenario or setting which could result in unethical behavior. Another ethically concerning way autonomous robots can be used is for surveillance. Because of their autonomy, these robots can survey large amounts of area without the need for human intervention. Autonomous surveillance robots can cause issues of privacy and could be abused by tyrannical governments to keep their citizens under complete surveillance, making sure they adhere to the laws set out by that government and controlling information at a large scale.

There are also some technical limitations that could pose some problems and ethical concerns. One problem that could arise comes from the use of heavy-weighted networks. Using heavy-weighted deep neural networks can be slow. Because of the lack of speed, predicting and making decisions in real time can be delayed to the point of concern. For time-sensitive tasks like search and rescue, making quick decisions is extremely crucial and the speed can be the difference between successfully completing a task and failing it. In these scenarios, this failure could even be life-threatening for those that depend on the network’s decisions. Another limitation of leveraging deep learning for autonomous robots, and leveraging deep learning in general, is adversarial methods specifically utilized to throw off deep and machine learning models. People with malicious intent could feed adversarial inputs into the model to have the model predict and make decisions erroneously which could lead to unethical behavior of the autonomous robot. Another technical limitation that could result in a less than ideal performance from an autonomous robot, is caused by the challenge of transferring simulation training to the real-world. There is still ongoing research to be able to effectively transfer simulation training to the real-world and further testing of our model is needed to determine the possibility of doing such. Nevertheless, the use of simulation has helped underrepresented groups conduct robotics research by providing a cost-effective alternative to training real-life robots. Overall, these technical limitations should always be considered, especially when entrusting autonomous robots with crucial tasks and high stakes.